Special Feature - Conservation & Management

Savannah Sparrow, a declining species throughout the West, by Becky Matsubara.

Using IMBCR Trends to Assess the Status of Species across Scales

Bird populations in North America have declined precipitously over the last 50 years (Rosenberg et al. 2019). Monitoring the status of both species of concern and formerly common but declining species is thus an important objective for management agencies. However, while national trends can help inform broad priorities and sound the alarm on range-wide declines, management typically occurs locally and regionally.

The IMBCR program has now collected avian occurrence and density data throughout the western United States for up to 17 years in some regions. These data enable the program to provide critical trend information on bird populations at multiple scales, from individual management units to state or region-wide. Below, we highlight two examples of these data for managers and decision-makers to monitor both existing priority species and common species in decline by accessing data via our recently updated Rocky Mountain Avian Data Center (RMADC).

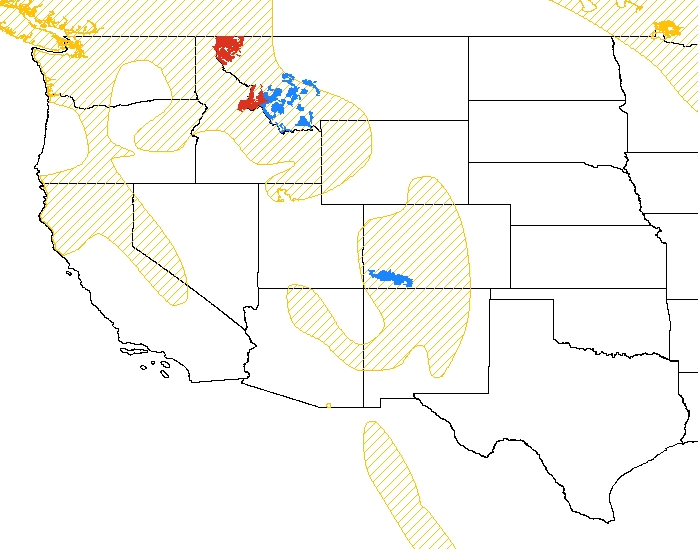

The Savannah Sparrow is not currently a priority species for conservation throughout its wide distribution (Wheelwright and Rising 2020). However, IMBCR trends show a decline across several populations within the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, from larger regions, like statewide across Colorado to specific management units, such as Yellowstone National Park. Given widespread declines at local and larger scales, efforts to prioritize the Savannah Sparrow may be warranted, at least in the western portion of the species’ range.

The Evening Grosbeak is a forest specialist and a Road to Recovery tipping point species that has experienced long term population declines (https://r2rbirds.org/tipping-point-species/). However, IMBCR data show variation in population trends throughout the Rockies. For example, populations in some USFS units, like Kootenai National Forest, have experienced declines, while populations in other units, like Helena National Forest, have increased since 2009. Monitoring populations at both local and regional scales can facilitate a mechanistic understanding of how local and regional processes may interact and affect populations, such as the Evening Grosbeak (Hewitt et al. 2007, Pavlacky et al. 2017).

Visit the Rocky Mountain Avian Data Center (https://apps.birdconservancy.org/rmadc/) to view trends for species of interest in your management area (click on “Explore the Data” to select filters of interest). IMBCR estimates are available for numerous focal areas or “strata”, where partners have invested in monitoring, such as the Bighorn National Forest in Wyoming. The “Superstratum” filter is helpful to find trends for broader regions or statewide (e.g., the BCR18-portion of Colorado) that provide context for strata. Filter trends by f-value >0.9 to view only robust estimates; these estimates are highlighted in yellow and estimates with a more stringent threshold of f >0.975 are shown in gold. Increasing trends are highlighted in blue, while decreasing trends are shown in red. Please note, we now provide two trend metrics: trend based on the annual density estimates and trend based on occupancy estimates. Although density and occupancy have different units, trend on either is interpreted the same way: as the percent population change per year during the monitoring period. Visit the “Tutorial” page for additional information on using the site and interpreting the estimates.